Fiction by Christopher Fulkerson

BLISS

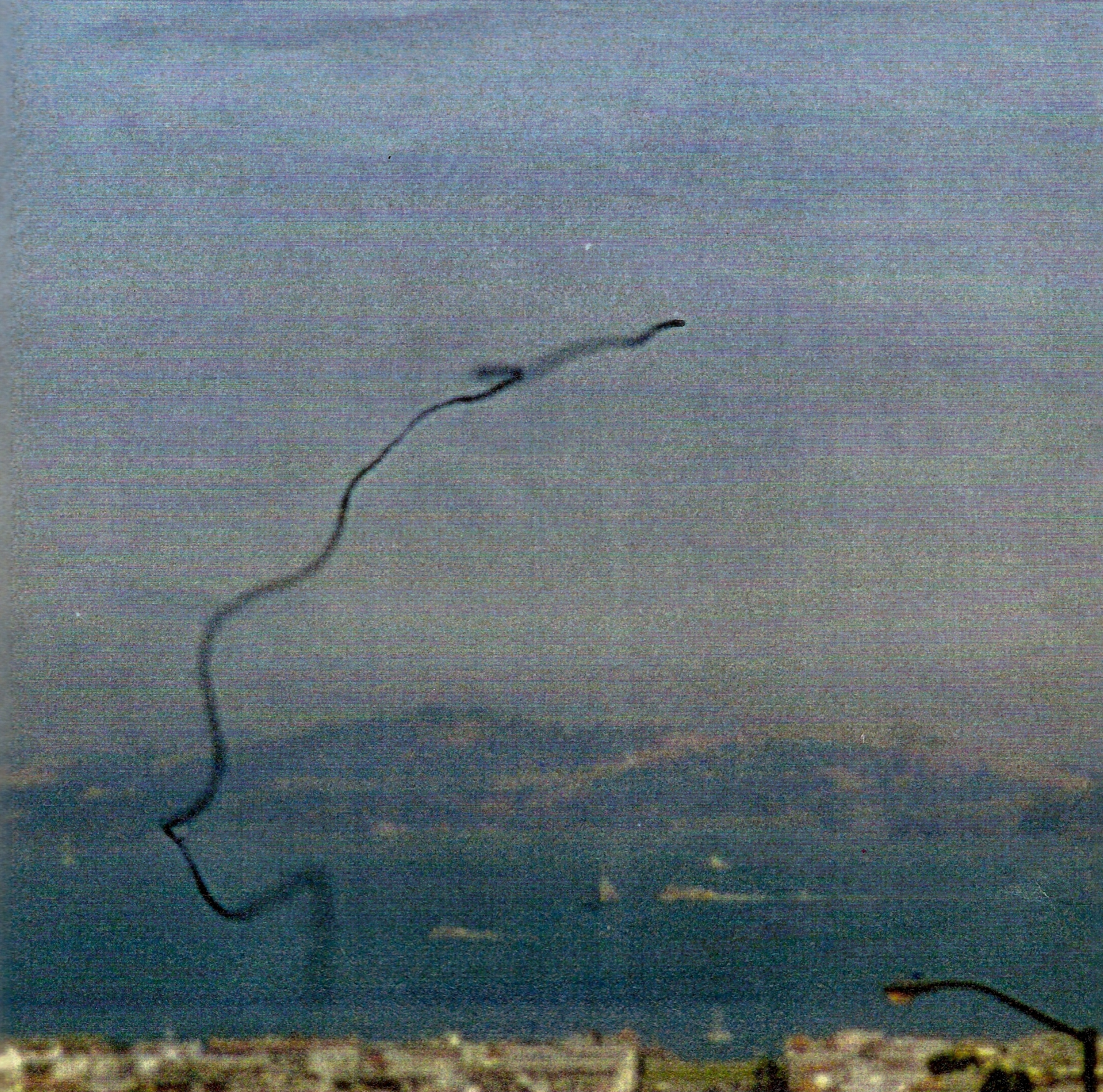

Unusual Aerial Phenomenon Over San Francisco Bay

Photograph by Christopher Fulkerson

Copyright 1999 by Christopher Fulkerson

All Rights Reserved

I suppose a man of my years isn’t allowed to blame others for his actions, but it was in fact my daughter’s encouragement that finally made me decide to go ahead and take my two-mast yacht, the Enoch, out for a trip on the Pacific. She probably wanted me to feel as though I was still a completely capable man. Never use a woman to prove yourself.

I was at a nadir of creative inventiveness and certainly needed some wind in my sails. I had agreed to conduct an advertising campaign for a friend who is a chewing gum manufacturer, but I was stumped. By this time in my retirement I only accepted jobs that intrigued me, or were for friends. I won’t say chewing gum intrigued me, but my confectioner buddy certainly had enthusiasm for it. How could anybody be that obsessive about ceaseless, pointless mastication, that ended only with an arbitrary decision to spit? But in his mind, his product was as necessary as the air he breathes, and as compelling as James Bond.

My friend had recently learned that Singapore has an anti-chewing gum law, and he was developing a persecution complex. I have ways to take pity on paranoid millionaires. I agreed to try to make everyone share his fantasy.

Normally, yachting is too demanding to think very much about advertising; that’s why I like yachting. But a few weeks earlier I had been forced by a change in domestic routine to ride on a municipal bus. Looking around, I began to think of riding in a vehicle as a different kind of “moving picture,” in which it was I, not the images on a screen, that moved. By the time I got to my destination I had decided I didn’t like bus riding after all, since it took too much time and gave me an aching posterior. Yet, though I was glad to be off that bus, I knew I had found an everyday experience that could help me in my creative work.

I decided that sailing, already a passion of mine, was a serene, even abstract form of the “moving picture” that I had just discovered for myself. The ocean speaks a language as expansive as the heavens, and as non-representational as a modern painting. It is a good thing for nature to aspire to the condition of art.

The ocean is one place where there is still no gaudiness, no advertising, no fire trucks, and, unless you bring a water-treading Jesus along, no jaywalkers. Clouds and winds become the only things that matter. The mind can play freely, and that was what I needed.

I mentioned these thoughts to Catharine and she suggested I go on a cruise. I decided my sons Arthur or Roland should help me. I suspected my age. As it turned out, Arthur, my eldest, was unavailable, since, lawyer that he is, he had to play the facial chameleon on Market Street. So Roland was glad to share the adventure.

We decided to set out from San Diego in February. Our agenda was a combination of hedonism and ambition. We headed south, toward the Galapagos, having no real plan to get there, at first hugging the coast.

We were making a slightly decadent time of it. No one can say the Enoch is a Spartan craft. It is crammed with labor-saving, and labor-avoiding, devices for those who relax best when pretending to work. There are two well-stocked “reefers,” as Roland properly calls refrigerators (you thought I meant something else?) and lots of booze.

At first, the weather was perfect. We were too few for mah-jong, so we just set the sails to take in the wind and put our feet up to take in the sun.

Just about the time I began to think there might be such a thing as sunburn on the feet bottoms, the weather began to look somewhat serious. There wasn’t much we could do. We struck the sails and called home. Not much was known. We were the only craft within hundreds of miles of our location.

I’m afraid we didn’t worry enough. We had been heading due south, and were due west of Panama. That meant that when the storm began to rise, we were as far from a coastline as we could be. Perhaps we should have sent out an SOS, but I was still telling myself “It can’t happen here.” And then, very suddenly, the ocean really swelled.

We tried using the wind to make for shore but then we realized we were too far out and should stow the rigging. We had to clear the deck fast. There were sails and ropes to put below. Roland was passing me the last armful of halyards and a sail that he had too hastily thrown together, and as he tossed them to me the rope fell to my feet just as I was stepping down the ladder. I saw something awful in his eyes as my feet got caught in the rope and I fell straight down the shaft. I heard Roland holler as I fell. I assumed his yell was in dismay at my fall.

I think I did in fact lose consciousness momentarily. I then remember raising my body all of a piece as if hoisted up under someone else’s control. Though I was aware of a kind of other-ness to my will as I tried to return to the task at hand, I can’t say I noticed supernatural effects that were stronger than the distortions of the raging storm. I just remember raising my body, torso and arms as one. It all felt like the sort of awful thing that happens during storms, but which one has to try to ignore and work through. I thought my problem had been the serious one, when I noticed that Roland’s yelling sounded somewhat distant.

I made it to the deck and looked around. Sure enough, he had gone over the side. He was thrashing about, choking and shouting. It did not look good. The last of the ropes were down below at the bottom of the stairs. I looked around for something to throw to Roland. There was a sort of overstuffed deck pad in the shape of a saddle that we used for lounging. I ripped it from its fastenings in a perfectly impersonal rage of violence and threw it to Roland. Saddles don’t float, and neither did the deck pad. It went straight down. Roland was still choking and flailing.

There was nothing left above to throw to him so despite being in a state of blind fear I went below to get a rope. I say blind, but as I went down I realized I absolutely must not repeat my earlier mistake and fall down the ladder. So in one of the moments of most heightened awareness in my life, I left the deck, went down, and brought up the ropes with which to save Roland’s life.

He was about fifty feet away. I thought I could never hope to throw a rope with sufficient accuracy. Forget any romance about cowboy lassos; the rope was too wet and the wind was too high. (Don’t ask me why there were no life savers nearby. Maybe the Enoch had spit them out.) I got a light, weighted bolo line. I knew the weighted monkey fist was too heavy to float, but I hoped I could throw it all the way to Roland. I paused an instant to be sure I wouldn’t miss, and threw it. He grabbed the line. In what looked like one motion he wrapped it around his arm several times. I pulled him back on board.

There were still some things to stow, and we weren’t out of danger, but there was nothing for it, we had to go below to take stock of ourselves. Roland had swallowed a lot of seawater and was vomiting; I had a headache that I couldn’t distinguish from the storm. Nevertheless, in the midst of it all, there was one very good moment for us, in which he looked shameful for having thrown me that awful armful, and I shook my head, thinking of the kitschy deck pad. What do you do when your ship is sinking? Why, tear it up and throw it overboard. We gave each other a big hug.

I was mighty relieved he wasn’t dead, but there was no time for effusive sentiments. Pretty soon we fitted the hatch cover and tried the radio. We managed to get through to somebody’s Spanish-speaking coast guard. We were told that the storm was not expected to last. We glanced at each other. Sheer waiting could mean hope.

As it happened we simply weathered the storm. We were blown north in the direction of Acapulco and by the time the wind was calmed that’s where we decided to put in. As we maneuvered into a berth we were inwardly flying on a cloud of relief, but of course we couldn’t show it. In order to give the appearance that we were as blase as any sea tars, I opened some chewing gum, and Roland and I were the chewingest, spittingest, most socially unconcerned sailors you ever saw. We laughed out loud with relief.

I had had my catharsis, and had made my realization. I decided that the chewing gum campaign should be a “guy” thing, all about how to look subtly crude, but rugged and capable of weathering any storm. Even a storm in which you throw life-saving deck furniture over the side. I would write a “real men chew chewing gum” campaign. In order to master the proper personality archetype, the better to demonstrate it to the ad execs, I began to practice obsessive, ceaseless, pointless mastication.

I was glad I was not in Singapore. Gum chewing is illegal in Singapore. I would not want to create a scene there.

**************

First posted 1/12/2010.