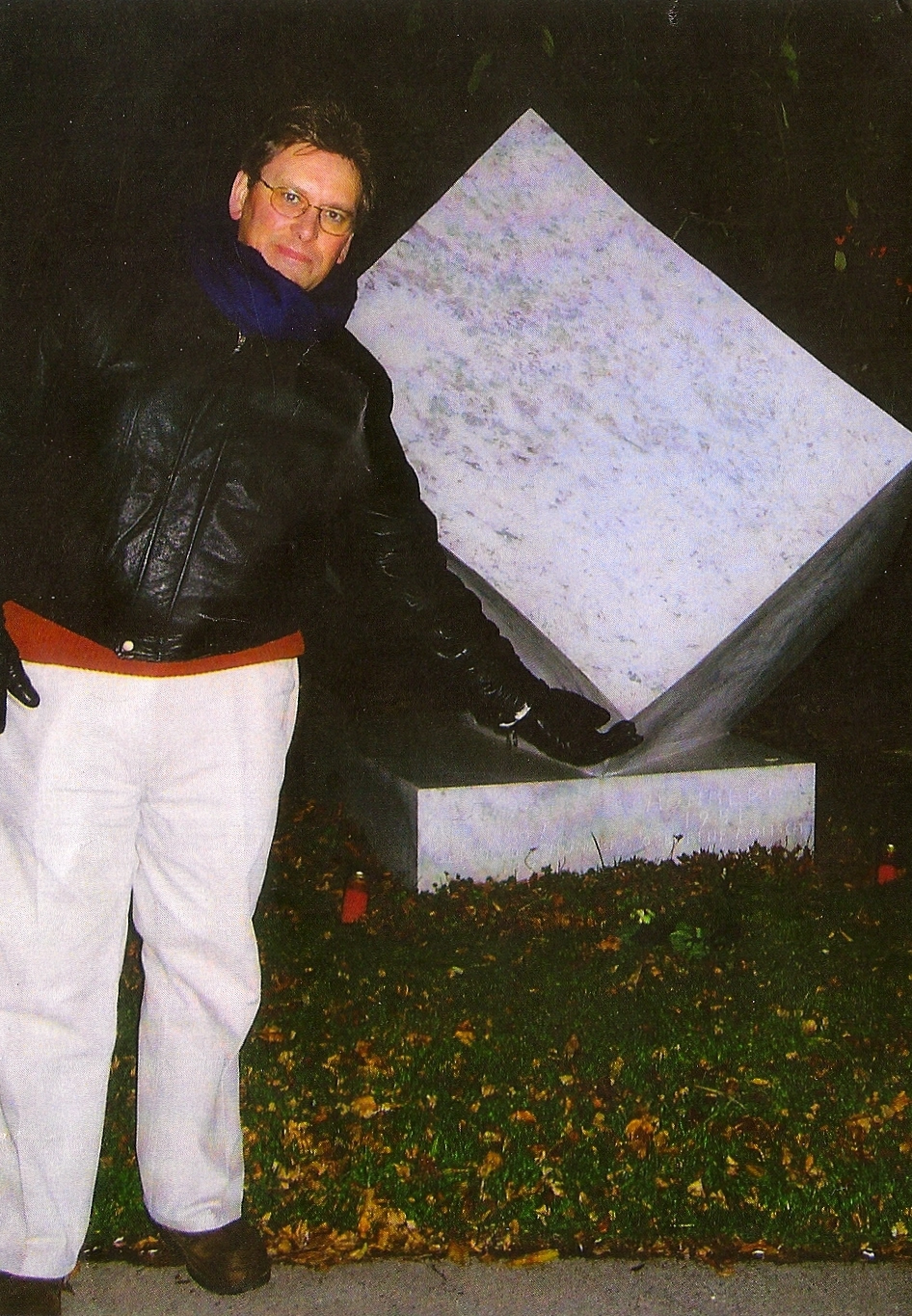

CF at the Grave of Arnold Schoenberg

Vienna, 2006

"You may never get to touch the Master,

but you can tickle his creatures."

Proverbs for Paranoids, I

from Gravity's Rainbow, by Thomas Pynchon

Quoted in CF's CELESTIAL SIXTIES I

Professors Barry Schutz and Thomas Fingar

Stanford Continuing Studies, June 2013, Revised July 2013

CLICK HERE for a version of this paper without the web elements

Or for a PDF of the paper

SUMMARY

With the largest economy in Europe and the fourth largest economy in the world, Germany is on a secure economic basis in the European Union. As a major player in automobile manufacture, and in the international politics attendant upon that industry, and for its peculiar situation as a twice-recovered state reliant on successful partnerships, Germany requires study. Its recent history and political structure make it unlikely to be a country with any more overt intelligence surprises than other rich nations, but its absorption of Communist East Germany and its proximity to Russia make it likely to be a sensitive area of covert intelligence for some time.

As a unified state, Germany enjoys more sustained prosperity than ever before. This is all the more remarkable as the absorption of East Germany meant West Germany’s acceptance of its severe economic and security problems. It is a world leader in research into renewable energy technology though (like all other nations) it has yet to bring this capacity to major economic fruition.

Germany’s present legal system specifies a number of criteria that make the accession to power of a dictator, such as was possible under the Weimar constitution during the early Twentieth Century, very unlikely. It also contains some important advances over other constitutions, such as the fact that not only citizens rights, but specifically human rights, are written into the Grundgesetz or Basic Law that is the German constitution.

Since the crisis in the euro, beginning in about 2009, the European Union has all but met its match in keeping its economic integrity. Germany has conspicuously emerged as a major creditor to the most indebted economy, that of Greece, and has incurred criticism, including from its own citizens, for this.

Germany is not among the American and Commonwealth nations’ “Five Eyes” partnership of sharing intelligence data and not spying on one another. It maintains its own vigilance about, but receives persistent international and domestic criticism for, its Imperial past. It has some business relationships with partners problematical to American political interests, such as with Arab states. However, despite likely security issues concerning the East German governmental and domestic absorption that occurred upon unification, there has been important, even occasionally clandestine, cooperation between the United States and Germany.

Germany’s “Back-story” In 250 Words

Around 1880 a movement toward “Pan-German” unification of Austria and Germany began to develop into a political question popularly debated as the “Big German” versus “Little German” unification of the two nations. According to the “Big German” model of unification, Austria would be the leader; in the “Little German” proposal, Germany would be the leader. The rise of Adolf Hitler was thus a variant of or compromise between these two perceived trends, and resulted in a state in which Germany was leader, but in which an Austrian would lead. Therefore, methods or legalities notwithstanding, and even though the American media still discusses it as a great surprise, within the German-speaking world the relatively peaceful ease of Hitler’s Anschluss into Austria was understandable, and popular expressions of favor toward the event were not necessarily feigned.

Hitler presented the Nazi state as a continuation of Germany as an “Imperial” state. Previously the German Chancellors had answered to the Emperor of Germany, a title which did not exist prior to the reign of the first employer, Wilhelm I, of Germany’s first Federal Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck. As the question of an Emperor’s authority, or perhaps lack thereof, arose, Hitler attempted to obviate the question by saying he was simply the “Fuehrer,” which has always been a quite non-official word that can mean anything from “Scout Leader” to “Tour Guide.”

Hitler revived the Empire’s earlier attempt to use military force to dominate Europe. With the Allied defeat of Hitler’s Axis, Germany became a straightforward nation-state. There is no longer discussion of a “German Empire.” In 1949 the title of the political leader was changed back to its brief (1866-1871) first term “Bundeskanzler,” or “Federal Chancellor,” thus avoiding the “Reich” in “Reichskanzler,” or “Imperial Chancellor. Since 2005 Angela Merkel has occupied this elected position. Her exact counterpart in Austria has the same title. In 1990 the parts of the country divided by World War Two into West and Soviet halves were unified; this event is popularly called either the “unification” or the “re-unification” of Germany.

The Structure of the German Political System

The Federal Government of Germany it is not unlike that of the United States. The legislature is bicameral. The Bundestag, or Federal parliament, which in size (About 600 seats) and manner of debate approximates the American House of Representatives, is parliamentary. However the Bundesrat, or Federal Council, which in size (About 70 seats) and as a council of the sixteen German States approximates the American Senate, is not parliamentary.

The German President is the Head of State, and the Chancellor is the Head of Government. The relationship between the twooffices is similar to that between a monarch and a Prime Minister. The Executive Branch of the gervernment of Germany is called the "Chancellory." Joachim Gauck has been President since 2012 and Angela Merkel Chancellor since 2005; she is in her second term. The largely ceremonial function of earlier sovereigns, which the Presidency replaced in 1919, does have some political powers, such as a veto power of Cabinet members proposed by the Chancellor. Like the British sovereigns, but not as invariably, the German Presidents have been reluctant to veto legislation presented to them for signature. Jurisdictional disputes within the Cabinet are by law settled by a majority vote of its membership. A close approximation to the American Secretary of State is the Minister of Foreign Affairs; this position is presently held by Guido Westerwelle. The Judiciary consists of five courts, three of which are in Berlin, while the two highest courts are in a small and deliberately out-of-the-way town, called Karlsruhe.

Germany's Political Partnerships

Germany is a member of the NATO military alliance and of two treaty organizations facilitating European political co-operation, namely the European Union, and the Schengen Area. It is also within the Eurozone, that part of the EU where the euro is the unit of currency. The European Union is a group of 27 nations nited by political and economic interests, and includes the United Kingdom. The recent crises in several EU states has left Germany subject to criticism for "wealth imbalances," and this specific topic will be discussed in a seperate section of this paper.

The Schengen Area consists of 22

of the EU countries (The U.K. for example not participating), and four others, and with Romania, Bulgaria and Cypress preparing to join. Members of the Schengen Area have abolished passport and immigration controls between their member states. The "United States of Europe" thus does not exist in the across-the-board way the United States of America does with free access between all states and one single currency. Nevertheless the freedom of motion allowed by the Schengen Area may contribute to a gradual resolution of some political issues of concern to Germany, such as the low birth rate, through facilitation of travel, which may in turn encourage immigration.

The German Economy

Though Germany has the largest economy in Europe and is a major exporter, its lack of portfolio diversification at the “macro level,” and of natural resources and energy, does not leave it free of the decisions of foreign nations, notably but not only the United States; like any mercantile nation, Germany is reliant upon the success of its partners. It is possible to express a thumbnail précis of Germany in terms of existing American states: as a bucolic nation reliant on auto manufacturing, which in turn relies on the existence of oil industries in what tend to be arid nations, Germany may be thought to resemble Michigan, reliant on the existence of a state like Texas.

Of Germany’s top ten corporations, three are automobile manufacturers. There are two each of chemical and electrical companies; marketing dominates the balance. None of these industries could exist without trade with foreign nations. Coal is Germany’s only abundant natural resource. Germany imports its oil, two-thirds of its energy and grows little of its own food: agriculture represents less that 1% of the economy. It may be noticed that an emphasis on auto manufacturing, and that market’s reliance in turn on oil (whether that of their own or their foreign customers), aligns Germany by default with the American “automotive Right,” and American efforts to bring about ecologically sustainable industry are likely to be resisted by Germany, its research into sustainable technology notwithstanding. Russia can be expected to encourage German reliance on a fossil-fuel based automotive industry. If the whole issue came to a conflict anywhere, Germany might side through action or inaction with international conventional auto and oil industry interests. Insofar as this conflict already exists economically and politically, Germany, like the United States at the present time, is not on the side of sustainability. Expressed in terms of the American bifurcation of political parties, as things stand, the largest German companies seem to be, from a practical viewpoint, for economic reasons, and speaking only very generally, more compatible with Republican than Democratic interests and agendas. With regard to sustainable manufacture, it is probable that international “industry understandings,” and even industrial espionage, complicate any major German change.

From its economic point of view, Germany’s dominance in Greece consists of maneuvering that country into austerities that Germany well knows from within living memory. On this particular point Germany’s insistence on austerity for Greece does not perhaps in the long run merit the accusation of “hypocritical.” A crucial question consists of whether Germans see a governmental responsibility for ensuring socio-economic security and socio-economic equality of the peoples of its fellow EU member states.

The German situation requires a far-sighted, candid and highly informed approach. Despite its national orientation to conventional industry, German ingenuity and potential for success in untried areas seems very good. A comparison of German patent applications per capita to those in the United States reveals that Germans apply for twice as many patents as do Americans. However, since there is a rising belief of the international sustainability movement that all internal combustion machines may be viewed as parts of a larger industrial and economic war machine, anyone’s sword-rattling anywhere about ecological concerns reveals Germany as still a major manufacturer of pollution-causing automobiles, which create markets for oil, and wars over oil. From this point of view, still tagged “liberal” in the US at present, Germany’s continued reliance upon the auto industry is consistent with those components of the current American political scenario which an increasing percentage of the populace perceive as undesirable.

An American public better informed about Germany might view it as merely a larger, better run, and cleaner Detroit. Whether they liked it that way or not might depend upon their preferences, and such political concerns are beyond the scope of this discussion. Since intentional air pollution in warfare is one of a variety of techniques collectively called “chemical,” it may be that the growing public awareness of pollution as a weapon that increasingly causes considerable civic damage - almost invariably to America - through severely inclement weather in the Caribbean Gulf and on the Eastern Seaboard, there may be a basis for an important claim: that causes of pollution, such as automobiles or coal-burning energy plants, are an aggression waiting to be officially recognized as such. Whereas in the United States, the failure of an industry may cause hardship but is unlikely to cause the collapse of the economy, Germany has no higher recourse against this possibility.

Germany is therefore capable of industrial change, but is likely to maintain the status quo through continued commerce along present lines. If the development of sustainable industry is a value, Germany at present has no problem with the problem of “too much business as usual.”

There is a bit of an information gap regarding the ease or difficulty with which German research into renewable energy and related technologies could be implemented by major industry. A host of such questions would perhaps only be answered by investment and sustained work. But perhaps it is safe to suggest that against the scenario of internal-combustion oriented German industry there is, thanks to German research, an already existing line of German potentiality which could define the nation’s role in the European Union with well-nigh operatic clarity.

German engineering abilities suggest it could, in fact, retool its automobile manufactory capability, if it wished. Germany could not only continue to be an economic leader but, thanks to sustainable technology, one with an adamantine ethical edge as well. It is probably more politically and scientifically feasible for Germany to “go green” than any other major player in the automobile and related industries. Germany has the capability to finance such operations.

Diplomatic work to achieve political understanding along these lines would be helpful. Now would be a good time for Germany to step forward with policies resulting in its own success with such ideas and products. There is certainly room in the market for a fully sustainable automobile. A “fully sustainable Volkswagen” could become the same kind of success that was the original “Bug.” Such a development could represent a quantum leap in an ethical German presence among the nations, and would not necessitate an uncontrolled revolution.

Germany could help everyone avoid using the world ecology as an economic “externality.” Germany could thus play a redemptive role for all, including itself, as a world-cleansing Brunnhilda, though sparing an immolation of herself and the rest of us. To do this is it would be necessary for Germany to avoid implementing defaults of existing American (or Russian, or Chinese) industrial policy.

Germany’s Dilemma In an Economically Distorted EU

The idea for some kind of union of European nations began to grow in the years following World War One in the minds of such politicians as Aristide Briand, Alexis Leger, and others, partly as a means of curbing Germany’s power. The EU as we know it began to be formalized as early as 1948 in a series of treaties growing out of defense and industrial concerns of its signatories. The 1958 Treaty of Rome began to direct these nations’ attention to more economic matters, and the 1992 Treaty of Maastricht gave more presence to the organization, and coined its name, the European Union. On “E-Day,” January 1, 1999, the EU brought its currency, called the euro, into existence, beginning with the participation of Finland and followed within an hour by ten other EU nations. Greece joined the euro in 2001; there are now 17 member states in the Eurozone. Better planning has existed: there are no exit clauses in the treaties that brought the eurozone together.

The crisis in the euro that has developed since 2009 is nothing if not breathtaking in its enormity, and Greece in particular has been a virtual black hole of economic and political problems. The world economic crisis that began with domestic real estate failure in the United States in 2007 did not seem to lead to immediate repercussions in the EU currency. The immediate cause of Greece’s problems seems to have been linked to conditions in Dubai. The situation is the euro’s first major crisis and test. Since by definition the value of the euro represents the stability of all EU member states, they are all in the crisis together.

The problem for Greece is greater than is discussed in conventional media, but is not beyond considerations well-known to both scholarly and popular quarters. Shipping is Greece’s largest industry – the Greek mercantile fleet accounts for 16% of the world’s total fleet – but it is fair to say that keeping Greek shipping honest is one of the most ancient and difficult governmental problems in any civilization, from the Argonauts to Onassis. The very idea of cleaning the Greek house is an enormous undertaking already enshrined in Greek myth as a “cleaning of the Augean Stables,” a task only a Hercules can complete, and is very unlikely to endure beyond a condition of high vigilance. Profound cultural reconditioning will be required to achieve success and make it endure.

From the beginning of the euro crisis media attention was drawn to Greek bad habits, with such remarks as “Make no mistake, it will be hard to change a culture where corruption and backhanders are rife.” “Tax evasion and corruption in Greece” is a page of its own at Wikipedia, which reports that 30 billion euros are lost in taxes each year to the Greek government. Tax evasion is a national Greek sport; Economist magazine pointed out that families with four children all in private schools, and who live in comfortable villas, claim to make only $20,000 a year.

By 2010 the European Commission, the executive body of the European Union, issued statistics revealing that both Greece and Italy had debts totaling 115% of their respective annual GDP, with high debt-to-GDP figures also for Germany (73%), the UK (68%), Ireland (64%), and Spain (53%). Of these nations, only Germany’s economy approximated the EU rule that a country’s deficit may only be 3% of its Gross Domestic Product. Italy’s deficit of 5% seemed relatively low compared to those of the U.K., Spain, and Portugal, all at around 11%, while Ireland’s deficit was at 14%.

Bailout deals were offered to Greece in May of 2011 and Ireland in November of that year. In 2011 a new bailout fund, called the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), set at half a trillion euros, was created by the EU to manage such crises. In May of that year Portugal was bailed out. A second Greek bailout was arranged, at which time German Chancellor Angela Merkel “Hailed the eurozone accord and said it was her country's duty to support the single European currency. ‘It is our historical duty to support the euro,’ Mrs. Merkel said. ‘The euro is good for us, the euro is part of Germany's economic success, and a Europe without the euro is unthinkable.’” In this first wave of loans Greece’s single largest creditor, after the EU itself, was France, which has made loans totaling about $60 billion, mostly from private banks, and Germany, which has loaned Greece about $40 billion, mostly from its government. The United Kingdom loaned $15 billion, and the United States helped out with about $7 billion.

By July 2011, the Greek debt was almost 150% of its GDP, France had reached 82% debt to its GDP, Belgium had reached 97% debt of its GDP, and the figures for all the other nations were worse, including for Germany and France. By August of 2011 European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso warned that “The sovereign debt crisis is spreading beyond the periphery of the eurozone.” In September another economic think-tank declared “The recovery has finished, we are now contracting. Things will deteriorate further in the coming months.”

Eventually Germany has become Greece’s principal creditor. “Germany has played a major role in every discussion revolving around the current Greek budgetary crisis. Not only has the country been singled out as the biggest creditor, and more generally as Europe’s paymaster, but it has also come under severe criticism for enforcing an export driven economic policy that condemns its European partners to negative trade balances with Berlin.”

Spain and Italy passed laws to require debt or deficit ceilings, apparently the first of their kind. In a move not unlike that of the US Fed, the European Central Bank began offering short-term emergency loans to European banks at low interest rates fixed at 1.5%. An effort to quadruple the funds available to the European Financial Stability Facility, the crisis fund run by the EU’s European Central Bank, failed. The EU bailout funds remain at around half a trillion euros.

In July 2011 BBC News Business reported that “The ECB and France had been particularly opposed to a restructuring and involving the private sector, but it was ultimately insisted on by Germany. Mr. Sarkozy played down the significance of the banks' participation in the aid package. ‘If the rating agencies are using the word you just used (default), it is not part of my vocabulary. Greece will pay its debt,’ he told reporters.” With these remarks we now come to a possible clue to the nature of Germany’s involvement with the Greek crisis, and some explanation for Greek public unrest. German “insistence” on a restructuring involving the private sector means that privatization of Greek debt is important to its preferences, even agenda. Germany’s private sector has contributed more to Greece than has the German government. By requiring that Greece be privatized, Germany has opened Greece as a market, by which privately-owned concerns, including its own citizens, may buy different kinds of ownership of Greece, mainly economic.

Some international leadership is clearly a facilitation of Middle East oil interests buying Europe. After a meeting of the minds between German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Nicholas Sarkozy, the Belgian bank Dexia, presented by the BBC as a major player in the loans being made in the private sector, was bailed out for $4.5 billion. Dexia’s average depositor keeps $20 million in the bank, while its Luxembourg unit was sold to a Qatari investment group.

A key reason for Germany’s policy of encouraging loans is probably the involvement of its private sector in the financing of the loans. As a state reduced to junk bond status Greece in particular pays exorbitant interest rates. Bloomberg has reported that Greece pays an interest rate of 177% on two-year government bonds issued in February 2012. Such payments can only be called usurious, but, in a realpolitick sense these rates may have a practical aspect, that is, they may be gauged according to privately known realities of Greek capability, and function as penalties or warnings. A gap in our knowledge exists in identifying exactly which loans at which interest rates are being taken out to whom; this is precisely the information that government would need to know the true economic situation. In any case Germany has been accused of serving its own national interests rather than facilitating a more ideal EU partnership, and hypocritically demanding austerities of Greece. Culturally however it may be said that on the specific point of austerities Germany went through some pretty awful austerities after World War Two so perhaps attention is better given to the simple question of economic exploitation itself. Wiki reports that “German economic historian Albrecht Ritschl describes his country as "king when it comes to debt. Calculated based on the amount of losses compared to economic performance, Germany was the biggest debt transgressor of the 20th century.”

Several waves of the present crisis have involved renegotiations of existing Greek debt. Greece has come under heavy criticism for swapping new bonds for old; on one such occasion Fitch ratings agency said it would have “no choice but to declare a default once the swap had been made.” Nevertheless, Fitch welcomed the Greek decision. German business also benefits from the low prices for its exports overseas created by the weak euro. One German economist states succinctly that German cultural conditioning is important. "In German, borrowing is 'schulden', [the same word for] ‘guilt.’ There is an attitude that if you have to borrow, there is something wrong with you," says David Kohl, deputy chief economist at Frankfurt-based Julius Baer bank.

Other international leadership has been empty cabal. In 2011, U.S. Treasury Timothy Geithner “called on European leaders to take urgent new steps to create a ‘firewall’ against the crisis spreading.” Just what this may mean is anybody’s guess, but within a Greek context one may wonder whether he is thinking of a new conflict like the ancient Battle of Thermopylae (Thermopylae means “Gates of Fire”). At about that time “UK Chancellor George Osborne… also warned that European leaders have six weeks to end the crisis.” The six weeks passed with no attention being paid to Chancellor Osborne’s ultimatum, and no consequences taken.

In January 2012 Standard and Poor’s lowered the credit rating of several EU nations. Germany maintained its AAA rating but France and Austria both lost theirs. A BBC economic commentator stated that “The downgrades increase the dependence of the big banks on finance from the ECB - and for the economic recovery of the eurozone, that's a very bad thing.” Three days later the agency lowered the rating of the EU bailout fund as well.

In late January 2012, 25 of the 27 EU nations signed a treaty to enforce budget discipline, the UK and Czech Republic refusing. This treaty allows for reviews by the European Court of Justice, the EU’s highest and oldest court, created by the first 1952 Treaty of Paris, in order to enforce compliance and impose fines. “The treaty also spells out the enhanced role of the European Commission in scrutinizing national budgets.” Germany “was particularly keen to get a binding treaty adopted to enforce budget rules.” Chancellor Angela Merkel stressed the agreement was built on a plurality of agreements already in hand; it was probably motivated to reassure Berlin that some durable laws set in stone would be in place before further German economic risks were undertaken, i.e., loans made.

Despite its apparent malleability the treaty was in fact a milestone. Nevertheless, there is clear evidence of “Euroscepticism,” a consistent part of the EU situation and an actual political opposition movement within the EU. Euroscepticism is particularly evident in the UK, and 15% of the British seats in the European Parliament are held by a “eurosceptic” group, the United Kingdom and Independence Party. British Prime Minister David Cameron announced that the treaty would “impose no obligations on the UK.” If this means the UK will not submit to EU Court review there may be considerable difficulties for the fate of the EU, at least as far as Britain is concerned. At 11% deficits, questions have been put as to whether Britain will have to face its own “Acropolis Now.”

Greek political instability has been so great that in one case a government, formed in May 2012 by judicial appointment, lasted only one month. New elections on June 17th, 2012 resulted in a narrow victory for the New Democracy Party, an older party which has become the “pro-Austerity” faction.

Germany is calling the Greek shots. The position of Germany in Greek decision making was made clear in a statement by British economist Gavin Hewlitt: “Already German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle has come out and said that the substance of the Greek reform bailout programme is non-negotiable. The message is clear; the austerity programme with its budget and spending cuts will stay. The German finance minister underlined that message when he said: ‘Greece's path will be neither short nor easy.’”

Spiegel magazine reports that in 2015 alone, $74 billion in Greek national debt will mature. Much of this debt is owed to Germany, and most of that, to private German banking concerns. Many economists believe that the best thing for Greece would be to leave the EU and start over. Should this happen Germany may be “guilty” of having forced Greece out, at some cost to itself. How it would benefit Germany to see Greece’s backside, unless it be through frank ownership, or participation in some German political program as yet little known, is a large and difficult question. Though the German leadership may be justified to believe it has set the course of Greece’s future, its own road is also not short nor easy, since its decisions are not widely popular in Germany. There have also been violent street demonstrations in Greece, which has seen a resurgence of the militant right, including of its militant right Golden Dawn party, an organization dating to 1970 and usually described as neo-Nazi, though it denies this association. The reality of such neo-Nazi claims is debated, and beyond the scope of this inquiry.

European security may be reliant on a clean Greece, acting as a buffer between Europe and the Muslim world, not unlike an Israel, but at one remove. However, there is a gap in our knowledge, as to the degree of Near East economic participation in a Greek situation that may only seem to be usually apparently devoid of Muslim involvement. Is German action a true “shoring up” of Europe’s interests, forcing Greece to swallow its medicine and prevent Greece from becoming a beachhead of conflicts towards its east, or is Germany merely acting to its own advantage? Popular opinion suggests the latter. If cynicism and doubts prevail about present German involvement with Greece, there is little that may be said about German economic control of Greece.

If a more positive atmosphere may be allowed as a paradigm, there is a strong case for sincerity in German involvement with Greece. German admiration of Greek culture was so strong than in the 18th Century German scholars retooled the German language after Greek models; Goethe’s greatest insult to a fellow German was to call him “Un-Greek,” and several major developments in German culture have involved a “back to Greece” component. This aspect of the matter is not likely to be absent from higher German awareness, though for most people in the world, including most Germans, there can be little doubt that it all comes down to accounting.

The German Military and Intelligence Community

A succinct statement of Intelligence scholar Mark M. Lowenthal cannot be improved upon: “German intelligence operates under a series of limitations, as does the German military, reflecting efforts to shun the history of the Nazi period and to avoid the conditions and actions that brought the Nazis to power.” The German constitution specifically requires that its military be only for “purely defensive” use. In practice this has included the use of the military as a crisis intervention force.

German court decisions discourage independent German military action outside of NATO that is not approved by the Parliament. There is a special office called the “Wehrbeauftragter,” which supposedly means “ombudsman” but in German fairly openly signifies a “Whistleblower’s Office” which reports to the parliament and not to the executive. This is specifically for soldiers to bypass the chain of command when they feel it is necessary, and petitioners are protected from disciplinary action.

There has been a trend for German politicians to rely increasingly on Germany’s Intelligence Community at the expense of its military, and to build this reliance into the nation’s political structure.

The Bundesnachrichtendienst, or BND, is called the “Federal Intelligence Agency,” and the nation’s only foreign intelligence service. It reports to the Chancellery through the Cabinet position of Head of the Chancellery and Minister for Special Tasks, currently held by Ronald Pofalla. For practical reasons it seems natural to assume that any Cabinet member, especially the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who works with the EU also has access to its separate Intelligence agency, the EU Intelligence Analysis Centre (EU INTCEN).

The question of the ease with which officers of the German government have access to the EU Intelligence Community requires attention. It seems clear that too many bureaucratic workarounds of reportage to the Minister for Special Tasks could result in major security problems for Germany. It is obvious that this office is of great importance in matters of international security.

The transition out of World War Two was intensely difficult and relied upon American patronage. A Wehrmacht general, Reinhard Gehlen, who had cooperated with the Americans, and his organization were, “after considerable head-scratching,” given third-tier organizational tasks and the operational name Project RUSTY, which was useful as a “waiting room” for German POWs being debriefed upon their return from Soviet POW camps. The CIA took charge in 1949 as part of an American effort to assure that German intelligence would not be susceptible to Soviet influence. Histories of the CIA leave the achievement of this goal much in doubt. The BND was established in 1956 within the framework of NATO. Its creation out of the American-founded postwar Project RUSTY was not popular with the Germans.

The chief of the BND is called its “President.” The agency is still in the process of re-invention even twenty years after the unification of West and East Germany. Like the United States, German intelligence operations centered during the Cold War on Soviet issues and have more recently been concerned with international terrorism, the proliferation of WMDs and organized crime. Occasionally BND operations receive media attention in European conflicts, such as when some BND officers were detected during the War in Kosovo and briefly held. Since it is closer to locales with actual conflict, Germany is among the states where perceptions of “public anxiety” are more among its intelligence and military doctrinal concerns than they are in American public awareness.

As the role of the German military has increased in crisis relief as part of its defense function, it has been found that the BND does not interface well with the German military, which has “gone begging” to other nations’ militaries for intelligence. The precise mechanisms for this phenomenon, and especially for its motivation, merit attention and explanation; it would be like our Congress shutting down the military not only through budget constraints, but operationally as well. In a move exactly opposite the rise in the United States of national and military intelligence at the expense of the CIA’s role, the German political leadership decided to give pride of place to the CIA-founded BND, going so far in 2007 as to entirely close down the Bundeswehr’s office of military intelligence and transfer only 270 of its 650 officers to the BND. Understandably, the German military viewed these as unwarranted cutbacks, lacking political vision or understanding. German Army and Navy intelligence does continue in functions specific to their services.

To the extent that the German military may be justified to lament its cutbacks, and because Russia remains an object of major American political concern and public expense, even the casual observer may remark that the postwar position of Germany as an important placeholder against Russia may be at risk. If this is a correct question it could signify considerable security risk for the United States.

An important intelligence question that requires investigation concerns the involvement of the IC of Russia, which now relies on oil sales for much of its economy, in maintaining the status quo of the international fossil-fuel market. Such a Russian policy would be more important to Russia’s actual source of income than its weapons research ever was during the Cold War. In this sense, though there seems no Cold War, the stakes have risen, not fallen, on Russia’s economic survival, and are now much more specific for Russia. Russia’s economic reliance on fossil fuels is relatively recent. GAZPROM, founded only in 1989, is the largest Russian extractor of natural gas and oil, and that one company alone accounted for 8% of Russia’s GDP in 2011.

Politically, recent German military cutbacks were in step with the refusal of Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder (in office 1998-2005) to commit Germany to the Iraq War, and which helped him to win the 2002 election. This was a “soft” refusal however, and during the Chancellorship of Angela Merkel a leak, probably in the BND, revealed that a clandestine cooperation between Germany and the United States had permitted Americans full and unremarked use of German bases during the conflict. In December 2008, retired Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer testified before a Parliamentary committee “I gave the green light in 2003.” All Germans involved maintain a firm denial of any German participation in American war-fighting, though this is directly contradicted by testimony of US General James Marks, who “Strongly emphasized they [the Germans] were ‘extremely useful’ to American war-fighting.’” The clear contradiction between these accounts suggests that there may be a gap in the “rules of engagement” as understood by Germans and Americans respectively. At least one German citizen (with dual Turkish citizenship), Murat Kurnaz, was detained in Guantanamo Bay (though released without charge); he figures in the 2008 John le Carre novel A Most Wanted Man.

Research is greatly needed into important details, including the demography of citizens’ covert loyalties, about the absorption of East Germany and the political and security matters of the post-Soviet and Warsaw Pact era, and related considerations. For the United States the major concern may be grossly stated as the question of the degree to which Germany may be penetrated by Russian intelligence. The era of German unification is part of an international situation so complex that it has generated its own academic niche in history studies, dubbed “1989 Studies.” (Even major parts of the American history leading up to it remain unwritten. ) Germany may have resolved many practical matters of this sort but whether these are secure by American standards and for partnership with the “Five Eyes” is another question, resolved at present, obviously, against Germany’s inclusion as a “Sixth Eye.” A major and continuing aspect of the project of unifying Germany consists in the consolidation of the CIA-founded West German BND with the KGB-collaborating and Warsaw Pact-bound East German Staatssicherheitsdienst, the infamous and efficient Stasi, which made considerable and well-documented use of psychological and clandestine operations and completely saturated East German society. With the fall of the German Democratic Republic, timely public protest and direct action prevented Stasi officers from destroying most of the agency’s documents. (Some reassembly of documents has been possible; in some cases “shredding” consisted only of tearing a document in two.) A special Federal office was created to preserve them. The civil situation and questions about the documents’ use approximates that of citizen’s rights and the use of such information during the era of the debriefing of the Nazis. In general, a policy of openness seems to prevail, but, again, the question of a future role for Germany as an American Intelligence Community partner may depend much on the security of its BND from Russian (and other) penetration inherited during unification.

If maintenance of non-sustainable energy is part of a Russian intelligence agenda in Germany, there would be plenty for former Stasi affiliates to do. Using organized labor to resist retooling industry is a skill already within the Marxist curriculum.

In summary in this section, it may be said that while German economic pre-eminence continues to grow and the nation’s skills at engineering and scholarship proceed apace, Germany has twice in 75 years had to absorb large, complex and risky re-patriations, first of the Nazis after World War Two, and secondly of the East Germans at unification. Due to its absorption of the KGB-affiliated Stasi, as well as an East German population commonly understood to have been teeming with infiltrators, it seems prudent to assume that German intelligence is still not sufficiently secure for full partnership with the “Five Eyes” nations.

German “Soft Power”

Germany is unlikely to participate in major independent conventional war-fighting in the near future. Its many laws and relationships prevent its being described as politically “mercurial” (but it is tempting to continue the planetary metaphor by describing the intelligence situation as “hot”). However, war in the sense of political and economic intervention is well within German capability, and from a negative paradigm may be thought to be already happening. Since several other large nations are already involved in maintaining the status quo, it may be that if industrial espionage is a problem Germany does not even have to be particularly involved with it in order to encourage it. Therefore, German national policy should be closely studied. Militarily, maneuvering the enemy to initiate a war is not only a very ancient part of the art, some of the best at it have been Germans. The German whistleblower function may be a solace to some observers that the German military remains hobbled against making any plans of aggressive war that may violate Germany’s Basic Law. But the evidence of increasing reliance upon its Intelligence Community, and the example of Germany’s economic involvement with Greece, may be an indication of increased German interest in “war by other means.” Through intelligence, two or more German enemies may be maneuvered into conflicts; what if one of them is America, or an American ally?

There is also the whole area of so-called “soft power,” a concept developed by Joseph Nye of Harvard University to describe the ability to attract and co-opt rather than coerce, use force or give money as a means of persuasion. The concept has considerable currency in international affairs and among analysts and statesmen. For example, in 2007, Chinese General Secretary Hu Jintao told the 17th Communist Party Congress that China needed to increase its soft power, and the US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates spoke of the need to enhance American soft power by "a dramatic increase in spending on the civilian instruments of national security – diplomacy, strategic communications, foreign assistance, civic action and economic reconstruction and development."

German soft power rates high in some popular media estimates. For example, in 2012 Monacle magazine released its third Soft Power Survey, listing Germany’s international ranking of soft power as third highest among twenty place holders, after the United Kingdom and the United States.

Some Observations and Some Game Changers

Germany is not itself a crisis-prone state, and though “another major global crisis cannot be ruled out,” for Germany, major surprises are only as likely as merchant frustration and the actions of non-state actors, which is to say, no more likely in the near future than for most rich nations. Military adventurism such as was possible under the Weimar Constitution is most unlikely.

It has been an assumption throughout this discussion that the BND does not usually function in a secretly clandestine or war-fighting way such as the CIA often functions. This may in fact be too much to assume of an agency developed through patronage by the CIA itself. Different assumptions could lead to quite different conclusions.

Though US estimates deny it, international over-reliance on existing “business as usual” may nevertheless have the overall effect of eventually promoting a clear Chinese hegemony, and this may lead to unpredictable volatility. Germany’s position as pro-fossil fuel technology may align it with both China and Russia. Also, unforseen developments in the automobile or oil industries could affect Germany considerably. Germany’s low birth rate might leave it vulnerable to the politics of nations affected by “Youth Bulge.” The open-door policy within the Schengen Area could contribute to this problem, as well as to the problem of the harboring and mobility of non-state actors.

Regional instability is a major “game changer” for nations and since Germany is reliant upon oil and other industries for natural resources it does not have, it remains vulnerable to the volatility of the political regions producing these resources. The prospect of a closed oil and chemical market could be enough of a reason for Germany to rethink and redesign its manufacturing, in order to be less reliant upon the stability of distant partners, particularly oil-producing nations. According to Global Trends 2030, “If the Islamic Republic maintains power over Iran and is able to develop nuclear weapons, the Middle East will face a highly unstable future. ” For many decades, the “security of vital resources,” usually a euphemism for the availability of oil, has been a major game changer. A closed Near East oil market would mean Germany’s automobile-buying customers would be more reliant on Russian-related oil markets.

A hamstrung military forces Germany to engage or participate in “war by other means,” and will prevent the German military from participating in the increasingly employed “three block war,” thereby rendering the German military even less useful, and leaving the state vulnerable to future accusations of humanitarian failure. The German-Greek relationship may in fact be understood this way. Germany’s military may even be in a downward spiral of cutbacks leading to further reliance in the IC leading to further cutbacks. A double standard may exist whereby German military actions are defined only according to obsolete or unprofessional concepts of war-fighting, while more flexible doctrine is permitted to the heirs of the Allied victors. There may be a point of diminishing Allied returns in a continuing label of “bad boys” for the German military. Increasingly, concepts of ethics enter even into war-fighting itself. USMC General James N. Mattis recently listed “ethical decision making” right along with initiative and aggressiveness among “timeless war-fighting qualities.” If ethical decision making is indeed denied the German military this is evidence of a double standard.

Meanwhile, if, with or without any particular nation’s discovered strategic purpose, internal combustion itself is finally understood to be the true “war machine,” which must then be shut down through a worldwide collective effort, Germany is, like everybody else, at this very moment freely participating in the actual threat. A sort of mirror imaging promoting the mutual status quo, in the form of an argument in favor of us and them continuing to carry on for economic reasons, may be preventing political and industrial progress. If so, there may be need of a note of warning, that Germany is not unlike, in certain specific ways, a de facto 51st American state (a designation which admittedly might accrue to several nations), which is subject to manipulation by status-quo preferences within American politics and industry. Germany is scarcely a loose cannon, but it may be thought to be precisely the kind of political component which Americans believe should be subject to political checks and balances.

(As a variant of the phenomenon of “mirror imaging,” especially in an era of any nation’s hegemony, it may be important to consider the degree to which foreign states are simply projections of the preferences of the hegemonic state. A resulting global or “multi-polar” state might not actually reflect the preferences of disparate nations, but those of a hegemonic state diversifying in its own interests. Thus the occasional talk about a future “multi-polar” world may be a distraction away from reality, and merely a soporific to those who are being maneuvered away from power–including perhaps the United States.)

Real or de facto German solidarity with existing industry may be a liability for Germany if the possibility of a sustainable automobile industry comes to fruition, but for some reason Germany chooses not participate. In short, Germany’s willingness to retool its factories to sustainable technology and products could be one of the major breakthroughs in international politics at this time, a real game changer for everyone. At present, the politics of the retooling of the world’s automobile industry might be described as the brinkmanship of avoiding brinkmanship, resolving into “business as usual.”

It must be considered that one of the areas of our ignorance may be of designs for eventual active or passive German-Russian economic collaboration against the interests of those who wish to deter global warming. It should not be forgotten that a stated German-Russian pact resulted in much of the surprise and devastation of World War Two. Will these parties resist the temptation to wealth and success that collaboration offers, at the expense of a wholesome world ecology? Russia, presently, cannot: it’s economic basis is “Largely that of a Third World state, exporting natural resources (oil, gas, timber), but not manufacturing anything with a significant market value.”

Due to the likelihood of Russian infiltration into German life, intelligence operations involving Germany could be risky whenever Russia is not a clear ally, and for only as long as it is an ally. Russia’s ability to, or even its interest in diversifying its economy is important to any known or unknown long-term scenario. Declassification of enough classified material about East Germany to empower the more vigilant and proactive component of the global community may be needed.

In terms of the face it puts forward to the world, Germany has for decades been culturally re-inventing itself after the model of other more popular countries, such as France or Austria, which tend to deliberately put forward only one or two particular cities as their cultural and political centers. Viewed as similar trends throughout history, the moving of most of the Federal Government, and more recently the massive move of the BND also, to Berlin is evidently part of a bid to make Berlin a “sub-national actor.”

Germany is making steady progress handling earlier failures in an international and cultural way consistent with the national character, and at present it’s only requisite project would seem to be to hew its deficit down. The German patronage of foreign conductors in Berlin, such as Daniel Barenboim and Sir Simon Rattle, can be viewed as both diplomatic and shrewd: Barenboim, a Jew, became even more famous by conducting, and recording, the complete works of Richard Wagner, known anti-Semite and figure of persistent but usually undeserved controversy regarding the Third Reich. The role of conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic is spoken of as “Chairman of the Board of Classical Music.” This notion came forward in the English-speaking world not during the tenure of any German, but during that of the Brit Sir Simon.

Mark M.Lowenthal, Intelligence, From Secrets to Polity, Fifth Edition, Los Angeles, Sage CQ Press, 2012, page 79.

Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, The Occult Roots of Nazism, NYU Press, New York, 1992. In Part One of his book, pages 7-31, Professor Goodrick-Clarke gives a précis of the “Pan-German Vision,” which should not be understood only by the title of his book.

William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, A History of Nazi Germany, With a New Afterword by the Author, Fawcett Crest, New York, 1950, 1960.

In English the official website is called simply The Federal Government. The Chancellor’s page is http://www.bundesregierung.de/Webs/Breg/EN/Chancellor/_node.html

“Economic power… depends on successful relations with others.” Mark M. Lowenthal, Intelligence, From Secrets to Polity, Fifth Edition, Page 263.

Figures are as of 2012 and are according to Wikipedia entries concerning patent applications and the figures of various nations. These figures are in each case of total national populations divided by patent applications, and are in this order: Japan at 126,659,683 people divided by 472, 417 applications, tied at four applications per thousand persons with South Korea at 50,004,441 persons divided by 187,454 applications; Germany ranking third at two persons per thousand making patent applications, that is, 80,333,700 persons divided by 172, 764 applications; the United States ranking fourth at one person per thousand making a patent application, that is, 316,077,000 persons making 432,298 applications; and China in fifth place at one person in ten thousand making a patent application, that is, 1,353,821,000 persons divided by 435,608 applications.

A new level of public awareness was signaled in a timely way by Bloomberg Journal shortly before the Obama re-election and in the wake of “Frankenstorm Sandy” with the full-page caption “It’s Global Warming, Stupid,” which seemed to be addressed to Mitt Romney. The grasp of global warming as a weapon is occasionally evident in other media.

http://thinkprogress.org/climate/2012/11/01/1122241/bloomberg-businessweek-its-global-warming-stupid/?mobile=nc

“In economics, an externality is a cost or benefit which results from an activity or transaction and which affects an otherwise uninvolved party who did not choose to incur that cost or benefit.” James Buchanan and William Craig Stubblebine, “Externality,” Economica 29 (116): 371-384 (November 1962). “Externalities are … external effects, external economies and diseconomies, spillovers and ‘neighborhood effects.’ For example, the upstream pulp mill which discharges effluent in the river thus reducing the score of fishing downstream is said to impose an externality on the fishermen. Externalities arise because of the non-existence of markets, i.e. there are no markets in clean air, peace and quiet and so on.” David W. Pearce, Editor, The MIT Dictionary of Modern Economics, Fourth Edition, Cambridge, The MIT Press, page 146.

Elizabeth Cameron, “Alexis Saint-Leger Leger,” in The Diplomats 1919-1939, Edited by Gordon A. Craig and Felix Gilbert, New Jersey, Princeton University Press, pages 378-404.

BBC News – Gavin Hewitt’s Europe, “Greece - the price of salvation” 12:55 UK time, Sunday, 2 May 2010.

14 February 2011 Last updated at 17:40 ET. “Eurozone agrees bail-out fund of 500bn euros,” http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-12460527. “The chairman of eurozone finance ministers, Jean-Claude Juncker, told a news conference: ‘We've already agreed on the volume of the lending capacity of the ESM. We've agreed on the amount of 500bn euros, and this will be subject to regular revision.’"

BBC News Business, 22 July 2011 Last updated at 16:30 ET. “Greece aid package boosts stock markets.”

BBC News Business, 4 August 2011 Last updated at 12:14 ET. “Euro crisis: Barroso warns debt crisis is spreading.”

Germany and the crisis of the periphery, by David Grodzki, 13/03/2012, The European Strategist, http://www.europeanstrategist.eu/2012/03/germany-and-the-crisis-of-the-periphery/

BBC News Business, 6 October 2011 Last updated at 17:03 ET “ECB holds interest rates and offers loans to banks.”

BBC News Business, 22 July 2011 Last updated at 16:30 ET. “Greece aid package boosts stock markets.”

BBC News Business, 28 April 2010. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/10089494

Spiegel Online International, June 21, 2011, 6:18 PM, Albrecht Ritschl, “Economic Historian: ‘Germany was biggest debt transgressor of 20th Century.”

BBC News Business, 22 July 2011 Last updated at 16:30 ET. “Greece aid package boosts stock markets.”

BBC News Business, 15 August 2012 Last updated at 19:26 ET “German economic strength: The secrets of success,” By Richard Anderson.

BBC News Business, 24 September 2011 Last updated at 10:07 ET “Geithner wants 'firewall' against crisis spreading.”

BBC News Business, 13 January 2012 Last updated at 17:57 ET “France loses AAA rating as euro governments downgraded.”

BBC News Business, 16 January 2012 Last updated at 14:46 ET “Standard & Poor's downgrades EU bailout fun EFSF.”

BBC News Business 30 January 2012 Last updated at 19:12 ET “EU summit: UK and Czechs refuse to join fiscal compact.”

BBC News Business, 18 June 2012 Last updated at 05:05 ET “Greece poll: Pro-bailout party's narrow win hailed,” Analysis by Gavin Hewlitt.

BBC News Business, 21 June 2011 Last updated at 08:52 ET “Greece takes the eurozone's future to the brink,” By Russell Hotten

Mark M.Lowenthal, Intelligence, From Secrets to Polity, Fifth Edition, Los Angeles, Sage CQ Press, 2012, page 368.

Wolfgang Krieger, The German Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND): Evolution and Current Policy Issues, in Loch K. Johnson, The Oxford Handbook of National Security Intelligence, Oxford, OUP, 2010, page 792.

“German Spy Affair Might Have Been Revenge,” Die Welt, June 10, 2013, at http://www.welt.de/english-news/article2806537/German-spy-affair-might-have-been-revenge.html

For a discussion see Sir Richard Dearlove, National Security and Public Anxiety: Our Changing Perceptions, in Loch K. Johnson, The Oxford Handbook of National Security Intelligence, Oxford, OUP, 2010, pages 33-42.

Wolfgang Krieger, The German Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND): Evolution and Current Policy Issues, in Loch K. Johnson, The Oxford Handbook of National Security Intelligence, Oxford, OUP, 2010, page 800-801.

Timothy Garton Ash, 1989! In The New York review of Books, November 5, 2009/Volume LVI, Number 17, Pages 4-8.

For example, when writing his epic “California Dream” history of the Golden State, Kevin Starr, the State Librarian Emeritus, skipped from the 1963 conclusion of the seventh volume to the 1990 beginning of his next published installment. Thus it is not so easy to find a full and continuous authoritative narrative of even local events. Hopefully Mr. Starr plans to span the missing 27 years.

Joseph Nye, Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power, New York, Basic Books, 1991. Joseph Nye, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics, Cambridge, Perseus Books, 2005.

Monacle Magazine remarks that “Germany has just about enough in its soft power arsenal.” This paramilitary metaphor is perfect for our present discussion, but as only a popular media summary Monacle is of course the least reliable source in this paper. Monacle’s comments about Germany’s use of business and the Goethe Institute as soft power seem reasonable enough, but it seems a courtesy to describe Monacle’s criteria of ranking as “asymmetrical” at best. According to this magazine, Britain is now the “most powerful nation in the world when it comes to ‘soft power’ and ‘public diplomacy,’” but this evaluation was achieved by allowing fashion to Italy, cuisine to France, and Harry Potter to Britain as viable forms of “soft power,” while holding the United States to food and health subsidies and climate change issues. http://howtoattractpublicsandinfluencestates.wordpress.com/2012/11/20/who-rules-the-world-monocles-top-twenty-overview/ In the study is a clear tendency for each type of “soft power” not to be repeated between countries listed, resulting in more of a suggestion of an apportionment of power than a fully reliable study.

http://monocle.com/film/affairs/soft-power-survey-2012/ The study therefore does not sustain close scrutiny, and some of its utterances are specious: for example, Monacle’s graphics indicate the United States is in second place, but falling, which seems plausible enough, yet the United Kingdom is in first place, and rising.

Global Trends 2030: Alternative Worlds, a Publication of the National Intelligence Council, Office of the Director of National Intelligence, December 2012, ISBN 978-1-929667-21-5, Page vi.

Global Trends 2030: Alternative Worlds, a Publication of the National Intelligence Council, Office of the Director of National Intelligence, December 2012, ISBN 978-1-929667-21-5, Introduction.

Global Trends 2030: Alternative Worlds, a Publication of the National Intelligence Council, Office of the Director of National Intelligence, December 2012, ISBN 978-1-929667-21-5, Page ix.

The Three Block War is a concept described by US Marine General Charles Krulak in the late 1990s to illustrate the complex spectrum of challenges likely to be faced by soldiers on the modern battlefield. In Krulak's example, soldiers may be required to conduct full scale military action, peacekeeping operations and humanitarian aid within the space of three contiguous city blocks. The thrust of the concept is that modern militaries must be trained to operate in all three conditions simultaneously, and that to do so, leadership training at the lowest levels needs to be high. The term has been referenced by CENTCOM commander General James Mattis, and has also been adopted by the British military, including former Chief of the General Staff, General Sir Mike Jackson and former Defence Secretary Geoff Hoon, and also by former Canadian Chief of Defence Staff Rick Hillier. This footnote comes entirely from the Wiki page on Three Block War: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_block_war

General James N. Mattis, USMC, Foreword to Operational Culture for the Warfighter, Principals and Applications, Barak A. Salmoni and Paula Holmes-Eber. Quantico, Marine Corps University Press, 2008, Page vii.

Mark M. Lowenthal, Intelligence, From Secrets to Polity, Fifth Edition, Los Angeles, Sage CQ Press, page 263.

Mercifully, the best discussion of this topic is relatively brief. In the Appendix, “Wagner’s Anti-Semitism,” to his fine study The Tristan Chord, Wagner and Philosophy, philosopher and former British MP Bryan Magee points out that Hitler’s fondness for Wagner was not shared by all the Nazi leadership. During the Third Reich, performances of Wagner’s works throughout Germany actually fell by one-third, which Wagner himself would have found alarming, and Hitler too made Wagner’s last work, Parsifal, illegal, with one or two exceptions, throughout Germany during the war. Hitler’s reasons for this are unknown. When Vienna staged Parsifal Hitler imposed a prohibitive duty on Germans, discouraging them from crossing the border to see the show. Bryan Magee, The Tristan Chord, Wagner and Philosophy, New York, Metropolitan Books, 2000, pages 343-380.

Uploaded July 17, 2013.